Monte Wolverton

GROWing disaster: the Fortune 500 goes farming

GRAIN.org reports: The world’s largest transnational food companies are rolling out a programme promising “market-based” solutions in agriculture. Vietnam’s highlands are the showcase for ‘GROW’, a global initiative under the World Economic Forum. A closer look reveals the programme’s real objective: to expand production of a handful of high-value commodities to profit a few corporations.

The world’s largest agribusiness corporations are rolling out a public-private partnership programme to take control of food and farming in the Global South.

Thousands of greenhouses cluster along the valleys of Lam Dong province in the central highlands of Vietnam. At night, the strong glow from their lights illuminates a flow of trucks carrying fruit, vegetables, flowers and herbs to Ho Chi Minh City or to nearby ports for export. Competition among traders here is intense. The climate is ideal for the production of a number of high-value cash crops, and companies fight to secure their supply of farmers’ products or for a share of the lucrative market in chemical inputs, seeds and farm equipment such as plastic greenhouse covers or drip irrigation piping.

Farming in the highlands is a high-stakes business. Each season, farmers gamble on which crop will pay the highest price or which new seed variety will reach the yields promised by dealers. Sometimes the payoffs are big. But losses resulting from crop failures, a sudden drop in prices or scams by traders are just as frequent. Debt weighs heavily on the area’s farmers.

Money is not the only problem. There’s a looming water crisis from the depletion of water tables and the pollution caused by pesticides and fertiliser run-off, which is generating a public health crisis. Land conflicts are escalating too, especially in the hills where indigenous communities live. Finally, there is a potential threat to food security from producing so many crops that local people don’t eat. Most farmers seem to agree that the government is doing little to address these challenges.

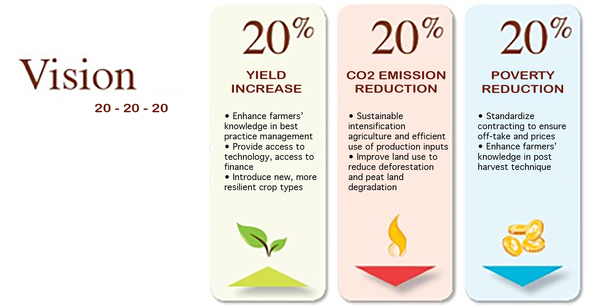

It is in this context that some of the world’s largest transnational food companies are rolling out a programme promising “market-based” solutions. Vietnam’s central highlands are the showcase for Grow Asia, an agricultural programme led by Nestlé, PepsiCo, Monsanto and other food and agribusiness giants. Grow Asia is the Southeast Asian leg of a global initiative under the World Economic Forum’s “New Vision for Agriculture”, which promises to increase food production, environmental sustainability and economic opportunity globally by 20 per cent each decade. Also under the Grow umbrella are Grow Africa, Grow Latin America and several national programmes.

Under a logic of “public-private partnership”, the multinational agribusiness companies participating in Grow are fostering close ties with governments in order to increase their control over markets and supply chains. While claiming to promote food security and benefit small farmers, Grow’s focus on a small number of high-value commodities exposes the programme’s real objective: to expand production of a handful of commodities to profit a handful of corporations.

Potato chips for food security?

The main Grow Asia project in Lam Dong promotes contract potato production linking small farmers with US-based food giant PepsiCo. Vietnam is a booming market for processed snacks, and PepsiCo is locked in a battle with South Korea’s Orion for the sale of potato chips. PepsiCo needs a particular potato variety for its Lay’s brand of chips and it has been trying to encourage Vietnam’s farmers to grow more of it. With local supply shortages, PepsiCo has relied on imports from Europe, but with chip sales expected to grow exponentially in the ASEAN region, the company wants to build up a more affordable local supply.

PepsiCo Vietnam’s Agronomy Development Manager, Nguyen Hong Hang, has spent nine years working with Lam Dong farmers to convince them to grow potatoes for his company. It has not been easy for him to meet PepsiCo’s target of increasing local production by 20 per cent each year. The profits for farmers have to match those they can get from other crops, and every year about a quarter of PepsiCo’s contract farmers drop out or are cut from the programme. Nguyen’s nine technical staff meet regularly with farmers to provide extension support and try to lower their production costs, mainly through bulk purchases of fertilisers and discounts for seed potatoes. Still, Nguyen worries that all his efforts could be in vain if the price for potatoes falls as a result of the free trade agreements Vietnam is implementing. In that case, PepsiCo would likely turn to imports or grow the potatoes itself, as it does in China.[1]

The benefit of the project for PepsiCo is clear: it secures the potatoes it needs for chips. But in terms of contributing to food security, the environment and poverty reduction, PepsiCo’s GROW project falls flat. First, potato chips are a danger to public health—not a source of nutrition. Second, PepsiCo’s contract farmers use as much fertiliser and pesticides as any other farmer. And while some farmers are making money by producing potatoes for PepsiCo, these farmers tended to be relatively wealthy even before the project, with little problem making comparable revenues from growing other crops.[2] Lastly, it is important to consider the indirect economic impact of shifting food preferences from traditional snack foods produced and sold by local vendors to processed foods controlled by foreign corporations.

Despite these issues, there is little awareness of the GROW programme and its potential impacts on the ground. PepsiCo’s contract potato farmers are not even aware that they are part of something called Grow Asia. The same goes for farmers participating in Grow Asia projects run by other companies in Vietnam. In reality, Grow Asia is little more than a set of contract farming projects—designed exclusively by its corporate members—that secure supplies of commodity crops for the companies. The GROW name exists to garner government and NGO support and to open yet another political space for corporations to mingle with politicians and lobby for business-friendly laws and regulations.

In Vietnam, this political space is a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Task Force made up of 15 US and European corporate members of Grow, which engages directly with the Minister of Agriculture. Through this task force, Grow corporations lobby to change national laws and regulations, and to win the support of the government and some civil society groups for their investment projects. For example, PepsiCo joined forces with other PPP Task Force member-companies to lobby for changes to Vietnam’s seed laws, in order to avoid the costly tests it must conduct before its potato varieties can be grown in the country.

Increasing the supply of Lay’s potato chips—and PepsiCo’s profits—is far more likely to undermine Vietnamese food security rather than enhance it. Yet such claims are being used to push similar Grow projects around the world in the interest of advancing an agenda of corporate control.

What is Grow?

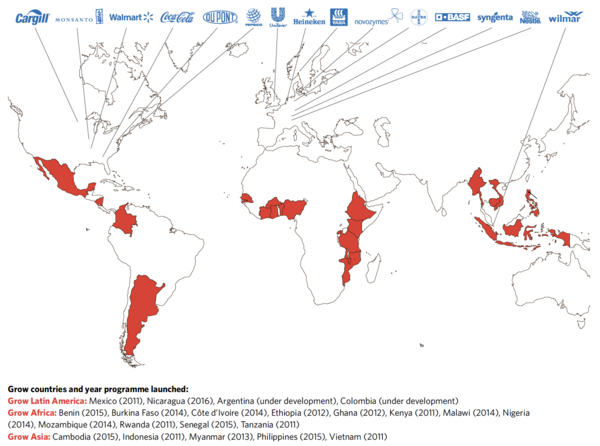

Grow is part of the New Vision for Agriculture, an initiative of the World Economic Forum (WEF) that was launched in 2009 and is led by 31 of the WEF’s “partner” companies involved in the food business, whether in agriculture, food processing or retail. Ninety per cent of these companies are based in the US and Europe, and none of them are from China, Brazil, Japan, Korea, Thailand or South Africa—countries that are also home to major food multinationals.[3] Yet the New Vision for Agriculture and its Grow programme is focused entirely on Latin America, Africa and Asia—the main growth markets for the global food industry (See map of Grow countries).

The New Vision for Agriculture is a vague document that calls for market-based approaches to increase global food production and ensure environmental sustainability.[4] Its main emphasis is on contract farming linking small farmers to multinational companies (and less, for instance, on corporate plantations). But there are no specifics and no obligations on its corporate members. More than anything, the New Vision for Agriculture is an effort to bring together a particular subset of multinational food and agriculture companies under a shared platform of common interests that they can collectively advance in key political fora. In other words, it’s a lobby group.

The New Vision for Agriculture has succeeded, through its programmes and other so-called multi stakeholder dialogues, in bringing the interests of its corporate members directly into some of the most influential agricultural policymaking circles. Through its Grow Africa programme, launched in June 2011, the New Vision’s corporations forged a partnership with the African Union and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) to establish and oversee “joint commitments among governments, donors and companies”. This was then brought into the G8 in 2012, resulting in the creation of the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa—a key instrument for coercing African governments into adopting corporate friendly policies.[5] The two initiatives are so closely intertwined that Grow Africa and the New Alliance issue their annual reports as a joint publication.[6]

The Grow Asia programme, meanwhile, is located within the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its Food Security Framework. It was launched at a Grow agriculture forum in 2014, with the participation of eight of the ten ASEAN country agriculture ministries, and the ASEAN Secretariat now collaborates directly in the implementation of its activities.[7]

In Latin America, the New Vision’s companies have their sights set on the Pacific Alliance (composed of Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) but it has so far been limited to a national programme in Mexico called the New Vision for Agricultural Development or VIDA (its Spanish acronym).[8] The programme operates in tight collaboration with the Mexican Secretariat of Agriculture (Sagarpa).[9] In June 2016, the World Economic Forum announced that three new Latin American countries had signed up to its New Vision for Agriculture initiative: Argentina, Nicaragua (through a new partnership called CultiVamos), and Colombia (through its Colombia Siembra programme).[10]

Grow may be a corporate led initiative, but it is funded by governments. GROW Africa is funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the UK’s Department of International Development (DFID) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), while Grow Asia is funded by the government of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the government of Canada’s Global Affairs Canada (GAC).[11]

Map: Grow countries and participating companies*

Grow in the fields

The “private” in the public-private partnerships that Grow promotes consists of the investments companies claim they will make. The companies say they plan to spend US$10 billion on Grow Africa investments alone, with US$1.2 billion already invested by the end of 2015. Such figures need to be put into perspective, however.[12] First, most of the corporate projects under the Grow umbrella are proposed investments, with no guarantee that they will be implemented. Second, they are company projects that are decided upon independently of Grow and other “stakeholders”. They are not like infrastructure PPPs, in which governments bring in private companies to help finance and operate social projects that they want to construct, such as hospitals or roads. Rather, Grow flips the PPP concept on its head: it is the companies that get public agencies—as well as NGOs and farmers’ organisations—to support their projects.

The focus of these projects is on a handful of high-value commodities managed by product-specific working groups. The working groups are typically co-led by a company and government body. These commodity working groups vary by country, but there are several commodities that target multiple countries such as rice, maize, potatoes, coffee, cacao and oil palm. It is not surprising that Grow projects are focused on building vertically integrated supply chains of commodity crops and input markets for corporate members, with a heavy emphasis on contract farming. In addition to creating farmer dependency on corporations, this speeds up the erosion of local and traditional biodiversity (for example, Monsanto and Syngenta’s maize project in Vietnam, see below). Some examples include:

- Unilever’s contract tea production project in Vietnam with two NGOs, the Rainforest Alliance and IDH. The project aims to increase Unilever’s procurement of high quality, certified tea in Vietnam to 30,000 – 35,000 tons per year.[13]

- Nestlé’s contract coffee growing project in Indonesia with Syngenta, Yara, Rainforest Alliance and Rabobank. The project will implement a financing scheme, in which farmers that have personal bank accounts will receive loans from Rabobank and administer these to other farmers to invest in coffee production.[14]

- Diageo’s contract barley farming project with the Ethiopian government’s Agricultural Transformation Agency. The agency will enlist 6,000 smallholder farmers to grow barley for Diageo and increase the company’s local supply of barley by 20 per cent.[15]

- Cargill and Monsanto’s contract maize farming project in Indonesia with the Bank Rakyat Indonesia and a government loan program called KKPE that provides farmers with low-interest loans as part of a national food security program. Under an agreement among Monsanto, Cargill, BRI and three farmers’ groups, KKPE credit is given to farmers to enable them to buy Monsanto’s hybrid seeds and produce maize for Cargill’s Indonesian feed mill.[16]

The Grow programme claims that these and other investments it promotes abide by the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (RAI).[17] But it does not hold its corporate members accountable for failures to comply, nor does it monitor or investigate compliance.[18] It merely advises and encourages its member companies to act responsibly and enlists certain NGOs and farmer groups to participate. Grow Asia, for example, has a Civil Society Council that “advises on ensuring positive societal and environmental outcomes”, but has no authority to ensure compliance.[19]

Furthermore, there is no serious process to assess how the corporate activities sponsored by Grow contribute to the WEF’s larger targets for food production, environmental performance and improved livelihoods. As with PepsiCo’s project in Vietnam, independent field investigations of some of these projects indicate that they are falling far short of expectations (see below).

Failing to grow: snapshots of Grow projects around the world

Monsanto and Syngenta’s maize project in Vietnam

One of Grow Asia’s projects in Vietnam is a Monsanto and Syngenta-led project to assist the Ministry of Agriculture in converting 668,000 ha from traditional rice production for food to hybrid maize production for animal feed within five years. Located in the country’s mountainous northern provinces, Monsanto says farmers’ profits will increase by 2.5 – 4 times as a result. But the conversion scheme has already had drastic impacts on the Xinh Mun people who live in this region. Over the past several years, many of them were encouraged to stop planting their traditional upland rice and to plant maize instead. Businessmen persuaded villagers to make the switch by offering them seeds and fertilisers, as well as household staples such as rice, salt, MSG, yarn and soup, in exchange for signing contracts to grow maize. Since many of them were illiterate, few were aware of what the contracts contained.

The farmers didn’t realise that they would have to repay the cost of the seeds at twice the price at harvest time, because of high interest rates, and that the prices would rise even further if they failed to pay on time. Farmers often ended up paying nearly three times the initial price for seeds. As a result, nearly 100 per cent of village households are now in debt, and 30 – 40 per cent of households have lost land to repay debts.[20]

AgDevCo’s irrigation hub in Ghana

Ghana is one of 12 African countries participating in Grow Africa. The government is proud of the 20 letters of intention that companies have signed for US$132 million worth of investments in the country under Grow Africa and the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa.[21] One of these investments, which Grow Africa highlights as an example of responsible investment, is led by the UK “impact investor” AgDevCo.

With political support from the government of Ghana and funding from the governments of the UK and the Netherlands, AgDevCo is constructing an “Irrigated Farm Hub’’ in Babator, in northern Ghana. The project began in 2014 when the company signed an agreement with traditional authorities giving it control over 10,300 ha for a period of 50 years with an option to renew for another 25 years.[22]

AgDevCo makes much of its “responsible” investment in farmlands in Africa, but a recent report claims the company paid traditional authorities so-called knocking fees in the process of acquiring these lands.[23] Moreover, local community members displaced by the project say they were promised it would involve them in a contract farming scheme; provide them with high yield seeds and irrigation water from the Black Volta River; and construct roads, schools and a health clinic. None of this has yet materialised and, although some compensation was paid to the farmers whose crops were destroyed to make way for the project, local people say they have been severely affected by the loss of land for food production and the decline in access to fish from the project’s use of their water sources.[24]

Mystery investment in Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire is a major target for multinational traders because of its production of export commodity crops like cacao and coffee. It’s also a lucrative market for rice imports, which have long been dominated by one of the world’s largest agricultural commodity traders: the privately owned French company, Louis Dreyfus Commodities (LDC).

Grow Africa claims 25 letters of intent were signed between Côte d’Ivoire and its member companies, worth US$963 million. One of these projects involves a major investment by LDC, with support from Rabobank, for local rice production. People in Côte d’Ivoire first heard about this project in January 2013 when LDC’s CEO Margarita Louis Dreyfus made a personal trip to Abidjan to meet with President Alassane Ouattara to sign a deal covering 100,000 – 200,000 ha of lands in the north of the country. Despite the immense size of the project, the details of the deal were never made public.

Since then, however, the project appears to have stalled. The Ministry of Agriculture maintains that the government and the company are in the process of enrolling farmers into contract production.[25] But farmers belonging to rice cooperatives in Korhogo, where the project is supposed to be located, say they already rejected the contracts offered by LDC. They say they did not like the terms and did not want to provide the company with any of their lands.[26] Meanwhile, LDC is silent on the project and continues to undercut local producers with cheap imported rice from Asia. Where it sources the local rice that it proudly displays at agribusiness fairs in the country is a mystery (see image 6).

Contract farming for Lay’s potato chips in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

In Indonesia, PepsiCo produces and markets its Lay’s potato chips through a joint venture with Indonesia’s largest food corporation, Indofood.[27] Like in Vietnam, Lay’s is struggling to build up a local supply of its potato variety. Indofood has responded by launching a project to develop potato farming with small farmers, which now operates as part of PISAgro, the Indonesian structure of Grow Asia.

One of Indofood’s projects under this project began in 2012 and involves farmers’ groups in five districts of Sembalun, Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara. Participating farmers must purchase seeds of Syngenta’s Atlantic potato variety, supplied by Indofood and imported from Australia. Training is provided by provincial government agencies, the Australian government and the Bank of Indonesia.

Unlike Indofood’s potato projects in other parts of Indonesia, in this case there are no contracts between the company and the farmers—just a verbal agreement with the head of each farmers’ group. Farmers say the absence of a contract gives them some flexibility to sell to local markets or other buyers, but it also allows Indofood to change its prices. In the 2016 season, farmers say the price offered by Indofood was half the price for potatoes in local markets. Farmers say they sold what they could on the local market, but most of their production had to be sold to Indofood to pay off debts for seed, fertiliser and administrative fees.[28]

High-tech horticulture and processed food exports in Mexico

Mexico’s “New vision for agro-food development” (VIDA or “life” by its Spanish acronym) includes the participation of 40 companies and Sagarpa (Mexico’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food) and aims to expand the production of cereals, oilseeds, fruits and vegetables, cocoa and coffee. It claims to have 85,000 participating farmers throughout México.

Like his counterparts in other Grow targeted countries, Mexico’s new Secretary of Agriculture José Calzada is dazzled by Grow’s marketing and shares its obsession with exports and corporate supply chains: “We are moving from traditional agriculture to a lot more mechanisation and technological ways of producing. Previously Mexico invested a lot to support ‘very traditional’ agriculture, whereas now most of the budget goes to support technology: greenhouse construction and high tech infrastructure”.[29]

For Calzada, this Mexican “horticultural miracle” goes hand in hand with the “processed food” miracle. If horticultural exports are surpassing oil earnings, processed food is also climbing. Currently, Mexico is one of the ten most important exporters of processed food.[30] Processed food and the export of horticultural crops are reshaping Mexican agriculture, with the production of raw materials such as starches and flours, high fructose corn syrup and edible oils on one hand, and greenhouse-grown berries, broccoli, cucumbers and tomatoes on the other. Small farmers are pulled into such schemes, but the benefits primarily accrue to large agribusiness corporations and a production model based on chemicals, hybrid seeds, mechanisation, high-tech environments and contracts that bind producers to sell exclusively to corporations.

This shift, according to Calzada, also requires the massive relocation of Mexican youth to work as labourers on corporate farms: “We need a lot of young people. Many of left the fields for the cities [sic]. We need for them to strategically move back […] We have 25 million people in rural areas and 7 million work in the fields”.[31] But this system of labour resembles slavery in many regards, conditions that have given rise to a number of farmworker protests over the past two years.[32]

Grow’s power grab

Grow’s greatest influence is not in the fields, but in backrooms. The regional and national structures that it has established provide its corporate members with direct access to Ministers and other high-level officials and provide them with opportunities to lobby for policy changes that favour their interests.

In Mozambique, for example, Grow Africa and USAID set up a Business Advisory Working Group (BAWG), which Grow Africa describes as “a private-sector led platform aimed at providing one voice of private-sector agribusinesses to government”. Agribusiness companies want the government to make it easier for them to acquire licenses for lands, known in Mozambique as DUATs (Direito do Uso e Aproveitamento da Terra). According to Grow Africa “the working group raised this issue with the Ministry of Land, Environment and Rural Development, which in turn wrote to provincial offices to fast-track DUAT issue”.[33] Grow Africa hopes to repeat this success in neighbouring Malawi where it has hired the South African branch of Deloitte to run a pilot project to set up a similar platform “to progress action on barriers to investment in the agriculture sector”.[34]

In Mexico, Grow has succeeded through its VIDA programme in formalising a collaboration with Sagarpa to develop “agro-cluster” contract farming schemes throughout the country. These schemes have even been integrated into Mexico’s National Development Plan for 2013 – 2018.[35] In Indonesia, PISAgro (Grow’s programme in Indonesia) is setting up a financial credit scheme called “innovative value chain scheme” to disburse small and medium loans to farmers in cooperation with the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (KADIN), the Indonesian Economists Association (ISEI) and Bank Rakyat Indonesia. The scheme is meant to provide farmers with finance for accessing high quality seeds and fertiliser as well as training in good agronomy practices.[36]

Grow structures most of its lobbying efforts around particular commodity crops that are of interest to its members such as maize, potatoes, coffee, cassava or cacao. At the national level, these take the form of commodity working groups involving companies and government agencies, such as the Potato Working Group in Indonesia led by Indofood or the Ghana Industrial Cassava Stakeholders Platform led by Olam and SABMiller. The companies within the commodity platforms can then work together to press for specific policy changes or government support.

Box 1. A lack of vision on climate change

One of the stated targets of the WEF’s New Vision for Agriculture is to reduce CO2 emissions from agriculture by 20 per cent per decade. Its approach is to implement more high tech systems based on “Climate Smart Agriculture”, and it is pursuing collaborations with NGOs and farmers’ organisations along these lines.

But evidence collected from the ground so far shows that Grow programmes have done little to reduce the largest global source of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production—the use of nitrogen fertilisers.[37] Farmers involved in the potato and maize projects in Vietnam and Indonesia, for example, have increased their use of fertilisers because the varieties they are contracted to cultivate require greater fertiliser applications than local crops and varieties.[38] In many GROW projects, farmers are even prescribed and supplied with nitrogen fertilisers by the Norwegian company Yara, one of the key corporations behind the WEF’s New Vision for Agriculture and a leading company in the Alliance for Climate Smart Agriculture. Indeed, there is a seamless interplay between these two corporate-dominated initiatives.

Grow’s focus on “connecting more countries to global value chains” and increasing the production of commodities for export and food processing is fundamentally at odds with real solutions to climate change. These global chains destroy low-emission, local food systems in favour of high emitting systems that require extensive transportation, processing, storage, packaging, refrigeration and marketing.[39]

Grow’s primary goal is to mobilise corporate investment for new forms of contract farming, re-packaged as “inclusive agribusiness”. While it has succeeded in convincing some farmers that they are the beneficiaries of this scheme, GROW projects in fact facilitate the corporate capture of food and agriculture systems and disempower small farmers.

The Grow programme helps a handful of corporations tap into government structures to access markets and producers like never before. In so doing, seed and agrochemical companies gain a secure market, with the help of government credits given to small farmers to buy their chemicals and hybrid seeds. Additionally, agribusiness companies save a lot of money by getting farmers to sign contracts with them instead of renting or leasing land for large-scale production. Lastly, corporations secure supplies of agriculture products and raw materials for their processed food operations from these contract farmers. For corporations, Grow offers a win-win-win scenario.

But there is no future for small farmers or small-scale food traders and processors in this vision, except where they can be made subservient to the main goal of large food corporations: securing supplies of cheap produce and raw material for processed food while selling more and more industrial farming inputs.

It is important to see this programme for what it is: a mechanism for corporate control. For farmers and civil society, the challenge is to recognise and reject these kinds of schemes that do nothing to tackle hunger, poverty or climate change. The solution lies with the communities and movements putting forward a vision of food sovereignty based in local markets, agro-biodiversity and agroecology.

References

[1] Interview with Nguyen Hong Hang, July 2016.

[2] Field visits to PepsiCo contract farmers, July 2016.

[3] This will change if the ChemChina acquisition of Syngenta is completed. The list of companies is available at: https://www.weforum.org/projects/new-vision-for-agriculture/

[5] Oxfam France, Action Contre la Faim and CCFD, “La Faim, un business comme un autre”, 2016, https://www.oxfamfrance.org/sites/default/files/file_attachments/rapport_nasan_bilan2016.pdf

[6] See their Joint Annual Progress Report for 2014-15 at: https://www.growafrica.com/node/23346

[7] The eight countries are Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Malaysia, Laos, Cambodia and Singapore.

[8] See: “World Economic Forum on Latin America: Advancing through a Renovation Agenda”, agenda agreed at the Riviera Maya, Mexico, 6 – 8 May 2015.

[9] World Economic Forum, “The Global Challenge on Food Security and Agriculture: A global initiative of the World Economic Forum”, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/IP/2016/NVA/WEF_GlobalChallenge_FoodSecurityandAgriculture_Overview.pdf

[10] World Economic Forum, “Latin American Agriculture Will Drive Growth and Food Security, Leaders Say”, 17 June 2015, https://www.weforum.org/press/2016/06/latin-american-agriculture-will-drive-growth-and-food-security-leaders-say/

[11] World Economic Forum, “The Global Challenge”, Op Cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Vietnam tea initiative. PPP for sustainable agriculture development. April 2015, https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/the-sustainable-living-plan/enhancing-livelihoods/inclusive-business/mapping-our-farmer-programmes/tea-vietnam.html

[14] Jenny Costelloe, “Sustainable Agriculture Partnerships: Something for Everyone”, 29 October 2015, http://www.growasia.org/resources/blogs/sustainable-agriculture-partnerships/

[16] Monsanto Indonesia, “Kontribusi Monsanto Indonesia PISAgro Kemitraan Jagung Berkelanjutan terhadap Ketahanan Pangan dan Kesejahteraan Petani”,5 November 2014, http://www.monsanto.com/global/id/berita-pandangan/pages/kontribusi-monsanto-indonesia-pisagro-kemitraan.aspx; Kontan, “Upaya mewujudkan swasembada pangan melalui PISAGRO”, 5 November 2014, http://industri.kontan.co.id/news/upaya-mewujudkan-swasembada-pangan-melalui-pisagro

[17] See: GRAIN, “Socially responsible farmland investment: a growing trap”, 14 October 2015, https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5294-socially-responsible-farmland-investment-a-growing-trap

[18] See, for example, GROW Africa’s position statement “Grow Africa, Responsible investment and land: Making good practice a competitive advantage”, August 2015, https://www.growafrica.com/sites/default/files/Position%20Statement-GA_RespInv_Land_%28FINAL%29.pdf

[19] The members are: AsiaDHRRA, Conservation International, Mercy Corps, Landesa, Rainforest Alliance, Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH), Swisscontact, The Nature Conservancy and World Vision Australia.

[20] Duong Dinh Tuong, “A high price: mounting debt means tragedy for tens of thousands of farmers in Vietnam”, GRAIN, 17 October 2016, https://www.grain.org/e/5570. The original article, in Vietnamese, is available at: http://m.nongnghiep.vn/nuoc-mat-noi-buon-va-bi-kich-cua-ngan-van-kiep-nguoi-trong-ngo-o-son-la-post174288.html

[21] New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition and GROW Africa Joint Progress Report 2014 – 2015, https://www.new-alliance.org/sites/default/files/resources/New%20Alliance%20Progress%20Report%202014-2015_0.pdf

[22] This is according to the lease agreement signed on 19 December 2014.

[23] Starr FM, “Ghana to lose over $3m project over land dispute”, 28 September 2016, http://starrfmonline.com/1.9931865. A “knocking fee” is an African expression that typically refers to a material or financial gift provided in exchange for a person’s consent in a process of negotiation. It can be seen as a form of bribery.

[24] Field visits, April 2016.

[25] Jeune Afrique, “Riziculture : Louis Dreyfus déchante en Côte d’Ivoire”, 7 January 2015, http://www.jeuneafrique.com/4310/economie/riziculture-louis-dreyfus-d-chante-en-c-te-d-ivoire/

[26] Interviews with rice farmers in northern Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

[27] Indofood is chair of the Potato Working Group for PISAgro/GROW Asia. It is the world’s largest maker of instant noodles and is partially owned by First Pacific Group, a Hong Kong based investment company.

[28] Field visit, September 2016.

[29] Thad Thompson, “Food exports surpass oil for Mexico”, The Produce News, 11 May 2016, http://www.theproducenews.com/the-produce-news-today-s-headlines/18727-food-exports-surpass-oil-for-mexico

[30] Mexico is one of the ten most important exporters of processed food. See: GRAIN, “Free Trade and Mexico junk food epidemic”, https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5170-free-trade-and-mexico-s-junk-food-epidemic

[31] Thad Thompson, “Food exports surpass oil for Mexico”, Op Cit.

[32] See the reporting and photographs of David Bacon: “Farm Workers in Two Countries Boycott Driscoll’s Berries”, The Progressive, 14 March 2016, http://www.progressive.org/news/2016/03/188606/farm-workers-two-countries-boycott-driscoll%E2%80%99s-berries; “Los trabajadores del Valle de San Quintín ya no están dispuestos a ser invisibles”, Desinformémonos, 24 January 2016, https://desinformemonos.org/los-trabajadores-del-valle-de-san-quintin-ya-no-estan-dispuestos-a-ser-invisibles/; The Reality check, photographs and stories, http://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.mx/; “Hemos decidido salir de las sombras” and “Migrantes oaxaqueños exigen cambios en los campos”, Ojarasca 222, October 2015, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2015/10/10/oja-sombras.html

[35] Sagarpa, “Impulsan Sagarpa y agroempresarios proyectos de seguridad alimentaria y desarrollo para pequeños y medianos productores”, http://sagarpa.gob.mx/saladeprensa/2012/Paginas/2013B605.aspx

[36] PISAgro fact sheet, “Building Indonesia food security through public private partnership”, http://www.goldenagri.com.sg/pdfs/News%20Releases/2016/PISAgro%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

[37] GRAIN, “The Exxons of agriculture”, September 2015, https://www.grain.org/e/5270

[38] Personal communication with GRAIN, July and August 2016.

[39] GRAIN and La Vía Campesina, “Food sovereignty: five steps to cool the planet and feed its people”, December 2014, https://www.grain.org/e/5102