How Tata Steel UK made a billion dollars from climate policies

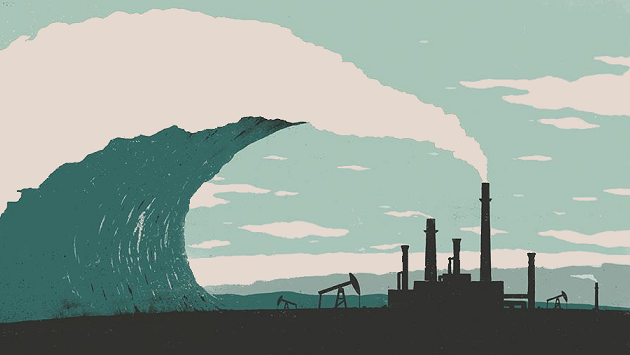

Nihar Gokhale reports: Tata Steel, which is selling its UK business, has indicated that energy – made expensive by climate change policies – caused its steel to be too costly. But, a new report says companies have made billions in profits from climate change policies like carbon-trading. Tata Steel itself made over a billion Euros.

Don’t blame climate change! Green policies made Tata Steel UK over a billion Euros

The claim

- Tata Steel is selling its UK business at the cost of hundreds of jobs

- It says energy prices, which have been made expensive by climate change policies, have made its steel too costly compared to China

On the contrary

- A research report says European companies have made billions of Euros in profits from climate change policies like carbon trading

- Tata Steel itself has made over a billion Euros between 2008 and 2014

- Explaining the policies that have helped the companies earn so much – like what is carbon trading?

- How Tata Steel made its billions by passing on a fictional charge to its customers

For years, developed countries have complained that climate change is bad news for their industries and jobs.

Even Tata Steel, which is selling its UK business at the cost of hundreds of jobs, has indicated that energy – made expensive by climate change policies – caused its steel to be too costly compared to China’s, whose firms enjoy cheaper energy.

On the contrary, a new research report says European companies have made billions in profits from climate change policies such as carbon trading. Tata Steel itself made over a billion Euros from 2008 to 2014.

So, just how did European firms exploit a climate policy to make windfall profits?

WHAT IS CARBON TRADING?

Carbon trading in Europe began in 2005, as a way to get industries to cut down carbon emissions.

Carbon trading works like this: a maximum target for carbon emissions is set, typically by scientists and governments. The target is fixed so that it causes minimal global warming.

This emissions target is to be shared among all emitters. Each industry is thus allocated a quota based on its requirements – some like coal-powered plants will naturally have a higher share, compared to a textile company.

Suppose a textile firm gets a quota of 10 tonnes of carbon emissions, but it needs to emit only seven tonnes. On the other hand, a coal power plant that needs to emit 20 tonnes may end up with a quota of only 17 tonnes.

Carbon trading is when the textile company sells the extra three tonnes from its quota (known as carbon credits) to the coal plant at some price. The textile firm makes some money, while the coal plant can function normally, and overall emissions have not increased.

Every year, companies have to prove that they have enough carbon credits to cover their year’s emissions.

The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) magnifies this trade on a Europe-level scale, where thousands of firms put up their extra carbon quotas for trading (like in a stock market), and thousands of firms who need to emit more than their quotas purchase them.

PROFITING FROM THE ETS

But this market too has its flaws. A Dutch research agency, CE Delft, has said in a recent study that European companies have made a killing from this system.

This ‘additional profit’ is seen as extra money the companies made by exploiting loopholes.

This has happened by three means:

Overallocation:

Companies were given more allocation than they ever required. In the example we used, the textile firm made money by selling three tonnes of carbon credits. But if the textile firm had been given a 20-tonne quota instead of 10, then the carbon trading system would make a windfall profit for it. Many companies are said to have lobbied extensively for extra allocations.

Using cheaper credits from elsewhere:

To comply with emission limits, companies are using cheap carbon credits from other markets. One example is the Clean Development Mechanism, where sustainable projects in developing countries (like the Delhi Metro) sell credits for the carbon emissions they helped save. If these are cheaper than credits on the ETS market, European companies use them instead, and sell their European credits in the market.

Charging customers for carbon:

The initial carbon credit allocations came for free. But what companies did – very roughly speaking – is they increased the price of their products, as if they paid a price for the quotas. But since this price is only notional, and not actual, the extra money is simply a huge profit.

SIZE OF THE PROFIT

The profit made through these three means is mind-boggling.

For example, from just the overallocation of credits, countries made 8 billion Euros from 2008 to 2014. In fact, all countries except Austria received more quota allocations than they needed.

Spanish firms made the biggest profits of about 1.6 billion Euros, because almost one-fourth of their carbon allocations were extra. Firms in the UK followed next, with a profit of 1 billion Euros on almost 100 tonnes of extra carbon emissions quota.

From using cheaper credits from elsewhere, about 630 million Euros were made between 2008 and 2012. Companies in Germany gained the most, cornering about one-third of the total profit.

HOW DID TATA STEEL BENEFIT?

Tata Steel UK made over 1.12 billion Euros as profit in 2008-2014, according to the study. (Although CE Delft says that its estimates for companies are not as accurate. The sector-wide numbers, which it says are accurate, were apportioned to different companies.)

The company made almost 163 million Euros from overallocation of quotas and 21 million Euros from buying cheaper carbon credits from elsewhere. But its biggest profits came from passing the (fictional) price of its quota to its steel buyers – an average profit of 943 million Euros.

The study gives a new angle to the Tata Steel saga unfolding in the UK.

Many have taken the opportunity to lambast the policies to tackle climate change, calling them a ‘major problem’ and ‘inconvenient truth’.

The argument is that costly energy policies are making British steel expensive in the world market, compared to China, where climate policies are not as strict, since it is not a developed nation at par with European ones.

But the new revelations turn this argument on its head in two ways:

- By showing that far from being losers, British firms including Tata Steel UK actually made huge profits from climate change policies.

- More interestingly, companies like Tata Steel UK actually made most profit by passing a fictional cost on to their buyers.

This means that the loss of competitiveness versus China is more a result of Tata Steel UK’s own greed than climate change policies.

Does a billion Euro profit seem as inconvenient now?