How Nepal Regenerated its Forests: Communities know their Forests Best

Report from NASA Earth Observatory

After relinquishing control of forests to the villages that depend on them, forest cover in Nepal nearly doubled.

In the 1970s, Nepal was facing an environmental crisis. Forests in Nepal’s hillsides were being degraded due to livestock grazing and fuelwood harvesting, which led to increased flooding and landslides. Without large-scale reforestation programs, a 1979 World Bank report warned, forests in the country’s hills would be largely gone by 1990.

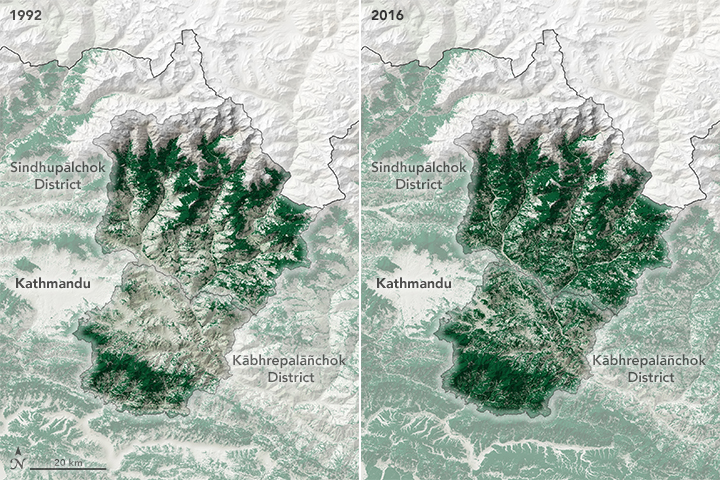

In the 1980s and 1990s, Nepal’s government began to reassess its national-level forest management practices, which led to a pivotal forestry act in 1993. This legislation allowed Nepal’s forest rangers to hand over national forests to community forest groups. The result of this community-led management, recent NASA-funded research has found, was a near-doubling of forest cover in the small mountainous country. The maps above show forest cover in Nepal in 1992 (top) and 2016 (bottom). Between these years, forest cover in the country almost doubled, from 26 percent to 45 percent. Using the long-term data record from Landsat satellites, along with in-depth interviews with people in Nepali villages, the research group found that community forest management was associated with the regrowth of forests. Most of the tree regrowth happened in middle-elevations, in the hills between the Himalayas and the plains of the Ganges River.

“Once communities started actively managing the forests, they grew back mainly as a result of natural regeneration,” said Jefferson Fox, the principal investigator of the NASA Land Cover Land Use Change project and Deputy Director of Research at the East-West Center in Hawaii. Before Nepal passed the 1993 forestry act, government management of forests was less active. “People were still using the forests,” Fox added, “they just weren’t allowed to actively manage them, and there was no incentive to do so.” As a result, the forests were heavily grazed by livestock and picked over for firewood. They became degraded. Under community forest management, local forest rangers worked with the community groups to develop plans outlining how they could develop and manage the forests. People were able to extract resources from the forests (fruits, medicine, fodder) and sell forest products, but the groups often restricted grazing and tree cutting, and they limited fuelwood harvests. Community members also actively patrolled forests to ensure they were being protected.

1992 – 2016

These maps show forest cover in Kābhrepalāñchok (Kabhre Palanchok) and Sindhupālchok (Sindhu Palchok), districts in the Bagmati Province east of Kathmandu. These districts were the focus of recent regional land cover change analysis because of their early adoption of community forestry. Beginning in the 1980s, the Australian government financed tree planting projects in these districts as well as the development of community forest groups. In many of the community forests, active management allowed trees to grow back naturally in the hills, but tree planting efforts were needed in lower elevation areas that were largely devoid of vegetation. One community forest (called Devithan or sacred grove in Nepali) lies to the east of Kābhrepalāñchok. Using Landsat data dating back to 1988, the research group found that the Devithan community forest had only 12 percent forest cover in 1988, which grew to 92 percent in 2016.

Although the Devithan community forest wasn’t a formal community forest until 2000, the community organized into an informal community forest management group (with laws limiting grazing and fuelwood collecting) after the 1993 forestry act. The study found that trees and vegetation rapidly regenerated, expanding canopy cover and the availability of fodder within the first few years of informal management. Within the boundaries of this community forest, about 25 percent of total forest regeneration happened before Nepal’s forest rangers formally recognized them as a community group. Today, community forests occupy nearly 2.3 million hectares—about a third of Nepal’s forest cover—and are managed by over 22,000 community forest groups comprising 3 million households. A 2016 United Nations report on the state of forests around the world found that three countries with the most annual gain in tree cover between 2010 and 2015 were the Philippines (with an annual growth rate of 3.3 percent), Chile (1.8 percent), and Lao PDR (0.9 percent). Within community forests of Kābhrepalāñchok and Sindhupālchok, forest growth between 2010 and 2015 was 1.84 percent.

(NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Van Den Hoek, J., et al. 2021. Story by Emily Cassidy.)

Communities know their forests best

(By Mukesh Pokhrel, 7th March 2022)

Thirty years ago, the Kumroj community forest in Kharahani was just open ground. The land had been cleared of timber by loggers and locals from the nearby Harari village grazed their cattle there. “There were no trees. We could easily see Padampur village, which is about five kilometers away,” said Rana Bahadur Shrestha, president of the Kumroj community forest. Now, the forest houses thousands of trees, along with plants, wildlife, and other biodiversity. The forest is managed by the local community, which in turn obtains many resources, like firewood, timber, thatch, and herbs from the forest.

The Baghmara Community Forest too was in the same state around 30 years ago. Trees had been cut down and the land had been encroached upon. “There was only bush, no trees. Land mafia had encroached the land and villagers had no access to it,” said Jit Bahadur Tamang, president of Baghmara community forest. Baghmara community forest too is now lush with trees and provides much-needed access to forest resources for the community. There are 70 or so buffer zone community forests around the Chitwan National Park and they have long been hailed as a global success story when it comes to maintaining forest cover and protecting wildlife with the active participation of local communities.

According to Biswo Nath Upreti, the first chief warden of the Chitwan National Park and former director-general of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, forest conditions were terrible around the park. Upreti, who was a team member of the border determination committee of the Chitwan National Park, says that while the forests inside the park itself were protected, the areas outside of its borders were prey to loggers and timber smugglers. It was only when the authority to manage and maintain these forests was handed over to local communities via the 1993 Forest Act that the trees began to flourish once again.

The same practice was also implemented around the Bardiya National Park. According to Ramesh Thapa, former chief warden of the Bardiya National Park, timber smuggling was rampant as there was no oversight and no proper management authority. Now, there are 145 buffer zone community forests around Bardiya National Park. According to the 2015 State of Nepal’s Forests report produced by the Department of Forest Research and Survey, forest cover accounted for nearly 45 percent of the total land area, up from around 29 percent in 1990s. Forestry experts attribute much of this success to community forestry.

“None of this would have been possible without the involvement of the community,” said Shrestha, president of the Kumroj community forest. “This forest was saved by the community. This shows that development of any kind cannot be possible without the participation of the community.” The transformation of Kumroj not only benefits the local community but also the national park’s wildlife. Animals, especially large predators, maintain large ‘home ranges’, areas where they spend their time and which contain all of the resources required for them to survive. The resurgence of the buffer zone community forests now allows them adequate home ranges that are not limited to the national park. “Wildlife habitats were limited only to the area of the national park,” Shrestha said. “But now wildlife can be seen easily in the community forest area.”

The Kumroj community forest covers approximately 1,300 hectares and provides habitats for dozens of species of birds and animals like tigers, rhinos, and deer. According to Ganesh Adhikari, information officer at the Chitwan National Park, more than 15 buffer zone community forests have developed into wildlife habitats, with Kumroj, Tikauli, Baghmara, Jankauli, and Namuna primary among them. According to Shanta Raj Gyawali, former director-general of the National Trust for Nature Conservation, the community forests have provided a natural extension for the national parks and that is facilitating the growth of Nepal’s wildlife numbers.

“If we are to increase the number of wildlife in the country, we must also extend conservation out of the national parks,” he said. “National parks cannot be the only habitat for wildlife. As we are seeing, wildlife is already frequently emerging out of the national parks.” The Nepal government initially began the buffer zone community forest concept to reduce the dependency of locals on the national parks for grass and wood. “The primary objective was to make it easier for people to obtain grass and wood without venturing into the parks,” said Sindhu Dhungana, a joint secretary at the Ministry of Forests and Environment. “The concept eventually went on to play an important role in conservation.”

Nepal formally launched the community forestry program in 1978 with the enactment of the Panchayat Forest Rules and the Panchayat Protected Forest Rules. But it was only with the 1993 Forest Act that community forests increased rapidly across the country, resulting in about 22,000 such forests. According to Dhungana, between 1962 and 1990, the nationalization of private forests and a rapidly increasing population resulted in a loss of a large amount of forest cover. The lack of private ownership, accompanied by a failure by the state to provide proper oversight, led to massive exploitation of the forests. While locals used the forests to meet food, fuel, and housing needs, timber smugglers and industrial interests mowed down large swathes of forests to sell the wood or clear the area to build it up.

Community forestry was enacted with the recognition that local communities are the primary stakeholders in the protection of the forests. Providing management authority to centralized bodies was often counterproductive as these bodies did not understand local needs and conservation efforts. As communities actively depend on the forests for their daily needs and livelihoods, they have a strong interest in protecting them. Local communities also tend to have long years of indigenous knowledge on forest protection and methods to harvest forest resources sustainably.

“Nepal’s forest area has increased due to protection by the community,” said Bharati Pathak, president of the Federation of Community Forest Users Groups Nepal. “If the people did not participate in conservation, Nepal would not be at the stage it is today.” Nepal’s forests today don’t just provide habitats for wildlife and resources for communities but also carbon credits to the tune of 500 million to 1 billion tonnes. In 2021, Nepal signed a deal with the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility that will allow the country to sell up to 9 million tonnes of carbon for up to $45 million.

Many buffer zone community forests are also investing in tourism and community development. The Kumroj buffer zone community forest makes up to Rs 40 million a year from tourism activities such as jungle safaris and sightseeing. Similarly, the Baghmara buffer zone community forest makes between Rs 30-40 million per year. The community forest user groups invest this income right back in the community. The Baghmara user group, for instance, has provided accident insurance of Rs 1 million each for 717 people in the Badreni village. Over 2,000 livestock have also been similarly insured.

“We’ve started with one village but we will extend the insurance program to more villages in the future,” said Tamang, president of the Baghmara community forest. “We have also invested in roads, education, and in efforts to reduce conflict between wildlife and humans.” Likewise, the Kumroj community forest has invested Rs 6,000 per family for a new water tap while pregnant women and new mothers receive Rs 2,000 as allowances. “We are also supporting schools and providing compensation to the families of victims of wildlife conflict,” said Shrestha. All of these achievements, however, stand at risk of being lost. FECOFUN, the umbrella organization of community forest user groups, has been protesting the planned expansion of protected areas for months now. Under the new federal system, various levels of government have planned to establish or expand existing protected areas, many of which infringe on the existing community forests. This would take authority away from the communities and place it in the hands of government authorities.

“These parks, reserves, buffer zones, environment protection areas, and forest protection areas are being created on lands managed by user groups. They are also leading to the destruction of community forests that have been historically protected and sustainably harvested by local communities,” Dil Raj Khanal, FECOFUN policy adviser told Monga Bay. “We request that the government bring an immediate stop to these activities.”

(Mukesh Pokhrel is a Kathmandu-based journalist. Pokhrel writes issues on climate change, environment, social, and political. He has two decades of experience in the Journalism field.)